How or why does the multiverse create new universes? Again, there are a number of different proposals for how this might happen, from eternal inflation which creates a sort of patchwork universe with bubble universes layered into the fabric of a singular flat multiverse (think of a quilt with the whole blanket being the multiverse and the patches being universes separated from each other by the knitting, but infinite in size) to a newer proposal by physicists Sean Carroll and Jennifer Chen called "Baby Universes," first discussed in 2004 here and elaborated upon by Carroll in his book From Eternity to Here.

In his book, Carroll explores the mysteries of the arrow of time. Why do we perceive time to be "flowing" in a single direction? The argument basically boils down to the second law of thermodynamics and entropy. The direction of time is regulated by the tendency of entropy (the amount of disorder in a system, or the amount of information needed to describe the state of a system, if you're into information theory) to increase. The fundamental laws of physics are ultimately reversible, so why we should perceive that eggs break, but don't spontaneously come back together really has to do with the likelihood of events occurring. If we took a box of evenly distributed gas and watched it for a while from within the box with no other frame of reference, we'd be hard pressed to say time exists at all. Nothing happens. We exist and watch a homogenous stew where nothing "ever" (a tricky word to use depending on how long you plan on watching) happens. If, however we were observers in a box of gas in which all the gas was nicely organized in one corner by a force field and then watched what happened when the force field turned off, we definitely would see something happen. Over time, the gas would spread itself out to equilibrium so that the density of gas was roughly the same everywhere in the box. While that was happening, we'd be able to "see" something - a process unfolding before our eyes that could tell us what was "before" (gas was organized in a corner) and what came "after" (gas was evenly distributed). It's the viewing of these processes that defines time for us observers in the box we call the universe.

Knowing this fact about our universe tells us a lot about the place we live. We know, if that's the case, that the entropy of the universe must have been relatively lower in the past for us to perceive that the entropy of the universe is increasing (which it always is according to the second law of thermodynamics) all the time. Why should that have been the case? If entropy always increases, why was the past a time of relatively low entropy? Did something make it that way? Some law of nature that we're unaware of? Also, if entropy always increases, can it increases without limit? And what happens, if we take our box of gas analogy and apply it to the universe, when we reach a point where all the matter in our universe is evenly distributed and relatively homogenous? Does nothing more happen once the universe plays out this cosmic evolution?

The problem with cyclic cosmologies is that contractions of the universe tend to involve a reversal of this well-established principal. If everything was neat in the beginning (condensed to a single point, a singularity) and has become more spread out and diffuse or messy since then (a la cosmic inflation), and this is a natural thing for the universe to do, how does the universe then decide to reverse this? Traditional thinking was that gravity would catch hold of inflation in the future and cause a re-compression of the universe, but think for a moment what that would mean for the arrow of time. Once gravity starts pulling things back in and reversing the expansion of the universe according to the clockwork laws of motion discovered by Isaac Newton, it would appear to us that the universe was operating in reverse! Light would leave telescopes and be absorbed by stars, which break down heavier elements into lighter ones only to dissipate into clouds of gas while you undigest and throw up your scrambled eggs before they uncook themselves and reassemble back into their shells and roll back into the hens from whence they came. The disorder of the universe would decrease if this were so, violating the cherished second law of thermodynamics while completely honoring the reversible laws of Newtonian mechanics. The observed acceleration of receding galaxies has kind of put a damper on people who still advocate a Big Crunch scenario.

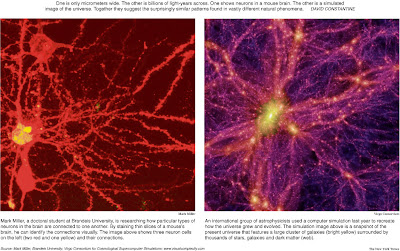

What Carroll and Chen have done is to provide a model where time always moves in a single direction, entropy always increases, yet occasionally, new big bangs happen in new universes that add to the total amount of disorder in the multiverse without bound. The thinking goes as follows: The big bang occurred some 14 billion years ago (I'll get around to proposed causes toward the end, it'll make more sense then) and an infinitely dense and energetic point of space-time begins to expand and cool forming matter and giving rise to the particular forces of physics we all know and love. As the universe expands due to the presence of a positive vacuum energy (the so-called dark energy responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe) it grows more diffuse until eventually it reaches thermal equilibrium trillions upon trillions of years from now. Stars have burnt themselves out and dissipated and everything has broken down so finely that we have a nice cosmic sand of background radiation, photons, electrons and other fundamental particles spread so thinly that they make today's definition of a vacuum seem ridiculously inadequate. At this point "nothing more happens" and the universe is dead. But statistically speaking, given an infinite amount of time, even tremendously unlikely events do happen. Subatomic particles may "coincidentally" come together in just the right way to form Boltzmann brains, single stars, even galaxies, but these aberrations would be statistical flukes in a sea of nothingness. But that's not all that's happening in the universe. The vacuum itself, even the vacuum of space today, is hardly a true, empty vacuum. In fact, random quantum fluctuations are occurring by the untold trillions in every cubic meter of space. Virtual particles spring into existence before self-annihilating fast enough so that no one would even know that the law of conservation of energy had ever been violated. According to proponents of the cosmological constant form of dark energy, the vacuum is also home to a repellant form of energy that is the root cause of the inflation of the universe. Inflation energy could be caused by a sort of false vacuum energy, imbuing the space in the universe with the energy necessary to expand. What appears to us to be a vacuum at it's lowest energy level may only be a relatively low level. Lower levels of vacuum energy could exist (see above). It's natural for this vacuum energy to seek out it's lowest energy level, and over extended periods of time it would, creating a true vacuum field in the universe. These energy fields, however, given an infinite amount of time would constantly fluctuate via the Uncertainty Principle in localized regions of space-time, creating bubbles of false vacuum again (equivalent to a ball spontaneously running uphill rather than down, but perhaps that's a bad analogy), that would naturally want to expand. Most of the time, the pressure from the space around these bubbles would cause them to collapse again, and prevent them from inflating the way small soap bubbles on the surface of your bath water are collapsed by the surface tension on the bubble and the air around pushing it back down. Every once in a while though, the energy level in these false vacuum pockets would be enough to overcome the "surface tension" and they would expand again. These regions would bubble "up" and separate themselves from our universe being briefly connected to ours through a wormhole, before that collapses as well and the bubble is free to "float off" on its own and continue to inflate free from the pressure of the surrounding space-time (see image above). The bubble would start off as a microscopic point with tremendously high energy (sound familiar?) and expand on it's own, cooling down so that some of the energy could form into matter. This new baby universe would be free to develop its own rules and laws of physics and sprout its own baby universes from its own future pockets of false vacuum energy. In this way, the universe continues to thermal equilibrium completely in line with the second law of thermodynamics while providing an out for the creation of new universes with "relatively" low entropy to expand and follow the second law to their own thermal equilibrium, increasing the total entropy of the multiverse ad infinitum. These events would be statistically exceedingly rare, and if they did occur, we wouldn't even realize it. All of the dramatic energy of expansion and explosion would happen in a universe detached from ours. As Carroll suggests,

What Carroll and Chen have done is to provide a model where time always moves in a single direction, entropy always increases, yet occasionally, new big bangs happen in new universes that add to the total amount of disorder in the multiverse without bound. The thinking goes as follows: The big bang occurred some 14 billion years ago (I'll get around to proposed causes toward the end, it'll make more sense then) and an infinitely dense and energetic point of space-time begins to expand and cool forming matter and giving rise to the particular forces of physics we all know and love. As the universe expands due to the presence of a positive vacuum energy (the so-called dark energy responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe) it grows more diffuse until eventually it reaches thermal equilibrium trillions upon trillions of years from now. Stars have burnt themselves out and dissipated and everything has broken down so finely that we have a nice cosmic sand of background radiation, photons, electrons and other fundamental particles spread so thinly that they make today's definition of a vacuum seem ridiculously inadequate. At this point "nothing more happens" and the universe is dead. But statistically speaking, given an infinite amount of time, even tremendously unlikely events do happen. Subatomic particles may "coincidentally" come together in just the right way to form Boltzmann brains, single stars, even galaxies, but these aberrations would be statistical flukes in a sea of nothingness. But that's not all that's happening in the universe. The vacuum itself, even the vacuum of space today, is hardly a true, empty vacuum. In fact, random quantum fluctuations are occurring by the untold trillions in every cubic meter of space. Virtual particles spring into existence before self-annihilating fast enough so that no one would even know that the law of conservation of energy had ever been violated. According to proponents of the cosmological constant form of dark energy, the vacuum is also home to a repellant form of energy that is the root cause of the inflation of the universe. Inflation energy could be caused by a sort of false vacuum energy, imbuing the space in the universe with the energy necessary to expand. What appears to us to be a vacuum at it's lowest energy level may only be a relatively low level. Lower levels of vacuum energy could exist (see above). It's natural for this vacuum energy to seek out it's lowest energy level, and over extended periods of time it would, creating a true vacuum field in the universe. These energy fields, however, given an infinite amount of time would constantly fluctuate via the Uncertainty Principle in localized regions of space-time, creating bubbles of false vacuum again (equivalent to a ball spontaneously running uphill rather than down, but perhaps that's a bad analogy), that would naturally want to expand. Most of the time, the pressure from the space around these bubbles would cause them to collapse again, and prevent them from inflating the way small soap bubbles on the surface of your bath water are collapsed by the surface tension on the bubble and the air around pushing it back down. Every once in a while though, the energy level in these false vacuum pockets would be enough to overcome the "surface tension" and they would expand again. These regions would bubble "up" and separate themselves from our universe being briefly connected to ours through a wormhole, before that collapses as well and the bubble is free to "float off" on its own and continue to inflate free from the pressure of the surrounding space-time (see image above). The bubble would start off as a microscopic point with tremendously high energy (sound familiar?) and expand on it's own, cooling down so that some of the energy could form into matter. This new baby universe would be free to develop its own rules and laws of physics and sprout its own baby universes from its own future pockets of false vacuum energy. In this way, the universe continues to thermal equilibrium completely in line with the second law of thermodynamics while providing an out for the creation of new universes with "relatively" low entropy to expand and follow the second law to their own thermal equilibrium, increasing the total entropy of the multiverse ad infinitum. These events would be statistically exceedingly rare, and if they did occur, we wouldn't even realize it. All of the dramatic energy of expansion and explosion would happen in a universe detached from ours. As Carroll suggests,"...from the point of view of an outside observer in the parent universe, the entire process is almost unnoticeable. What it looks like is a fluctuation of thermal particles that come together to form a tiny region of very high density - in fact, a black hole. But it's a microscopic black hole, with a tiny entropy , which then evaporates via Hawking radiation as quickly as it formed. The birth of a baby universe is much less traumatic than the birth of a baby human.

Indeed, if this story is true, a baby universe could be born right in the room where you're reading this book, and you would never notice." (Carroll, 358)Which of course, begs the question: has it happened before? Carroll, again,

"It's not very likely; in all the spacetime of the universe we can currently observe, chances are it never happened."(Carroll, 359)But apparently, it could.

Carroll, Sean. From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time. London: Plume Books, 2010.